Update from March 3rd, 2024

This article is rather old and hasn’t aged as well, as I’d hoped.

Since the creation of this article, I have had numerous issues with large mail providers (namely Google and Microsoft) banning my mail server without any warning.

This is obviously expected, since they don’t have much reason to notify potential spammers that they’ve been blocked. But, it created a lot of friction when I send an important e-mail, only to find that it was never received.

While setting up a mail server like this can be interesting - and might also align better with some of your own ideals - it’s simply infeasible in the current day. And while it’s an unfortunate reality, there’s little to do about it.

Depending on your needs, I recommend using one of the larger mail providers. Some of them have features that are more catered to privacy-focused individuals, namely Tuta, mailbox, FastMail (although I haven’t used any of these).

Preface

E-mail is ancient and complex. You’re going to see what I mean, when you’re done here. That’s usually why hosted services like Yahoo, Gmail and Hotmail gravitate so many people. It’s so simple to use and there’s barely any setup. But then… Why would anyone want to host their own mail server? That’s insane!

Well, there might be many reasons to host your mail-server. You want ultimate control, you have an organization that requires it or, like me, you want to self-host as much as possible. Maybe you want to use e-mail like it was supposed to, decentralized. Whatever your reason, you might find some useful tips here.

I’ve recently setup a (relatively) complete mail-server. Most of the work was done for me, however, so I never needed to fumble around with configuration files or anything. Most of the work comes from setting up DNS-records, firewalls and removing myself from blocklists. You know, the fun stuff.

This article isn’t about setting up Postfix, Dovecot, etc. Don’t worry, you don’t need to mess around with configuration files, if you don’t want to. We will use prebuilt solutions, which are (F)OSS. Currently, all solutions are free, both for individuals and commercially. This might change in the future, however, so check the license, if unsure.

Requirements

Infrastructure

- Access on port 25/TCP (some ISPs don’t allow this)

- Dedicated IP-address

- Static IP-address

- Reverse DNS capability, also known as a PTR record

Some of these requirements can be met, using your own ISP. However, some ISPs might require an enterprise connection for Reverse DNS. If this is the case, hosting on your own home-network will be tricky. You will most likely still receive e-mail, but most, if not all, sent e-mail will go into the dreaded Spam-folder.

Many people use Virtual Private Servers or VPSs. Most, if not all, VPS-providers fulfill the above list of requirements. I’m currently hosting my VPS with DigitalOcean, using a Ubuntu 20.04 LTS image. I can’t possibly include instructions for all VPS-providers, but I will include a simple walkthrough with DigitalOcean. If you’re unsure, search your way out.

Which hardware you need, is up to your use of that hardware. If you’re the only user, 1 GB of RAM should be fine. Of not, either upgrade the RAM or add some swap.

DNS

Now, it should be obvious, but you’re gonna need a domain. On top of that, you need advanced configuration of the DNS. Usually, your domain-provider (aka., the place you bought your domain), will allow you to change the nameservers. Here, I’ll do it using Cloudflare, which is free, customizable and supports everything we need.

Cloudflare Sign-up: https://dash.cloudflare.com/sign-up?pt=f

Complete mail solutions

As said before, we’re going to be using a prebuilt solution. This saves us from configuring every single service that’s needed. No reason to reinvent the wheel, if at all possible.

For most compatibility, we’re going to prioritize Docker-compatible solutions. Non-Docker installations can corrupt your environment, if you don’t know what you’re doing.

The most popular solutions:

- Mail-in-a-Box requires a machine, dedicated to run the mail-server, which is limiting.

- Not Dockerized. While third-party images are available, development seems to have halted.

- Provides good setup instructions for DNS.

- Includes instructions for advanced use-cases, including backups, spam-filters, setup of mail-clients, etc.

- Provides great admin UI for managing 2FA, DNS keys, users, etc.

- Uses docker-compose.

- Relatively similar to Mailcow.

- Compared to Mailcow, it the setup is more in-depth.

- Provides great admin UI for managing DNS keys, users, aliases, etc.

- Allows for docker-compose

- No 2FA, yet. Might change in the future.

I use Mailu as it’s the one I’ve used the most. However, if you haven’t tried anything, I’d recommend using Mailcow.

Server setup

After you’ve chosen your VPS-provider (or lack thereof, if you’re hosting at home) and DNS provider, you need to setup the server. To avoid confusion, this is the infrastructure I’m going with:

- VPS Host: DigitalOcean

- DNS Provider: Cloudflare DNS

- Distribution: Ubuntu 20.04 LTS

- Mail Solution: Mailu 1.9

VPS setup

Depending on your VPS provider, you might need to setup your Reverse DNS, when you’re creating the VPS.

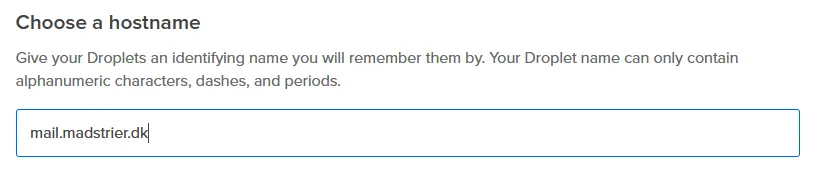

On DigitalOcean, to map a PTR record, you need to name the Droplet after your mail-domain. In my case, mail.maxtrier.dk

After your Droplet is setup, your Reverse DNS (PTR) record should be created. Depending on your DNS server, it might take up to 6 hours to propagate. If you’re using DigitalOcean’s DNS servers, your rDNS should point to your mail-domain, right away. You can test it by running

dig -x 206.81.31.168 +noall +answerWhere 206.81.31.168 is your Droplet’s IP-address, of course. It should point to your mail-domain.

168.31.81.206.in-addr.arpa. 1773 IN PTR mail.madstrier.dk.DNS

Now that your VPS is up and running, you should set your initial DNS records. We will do this in parts, so we will start with the simplest ones.

A-record

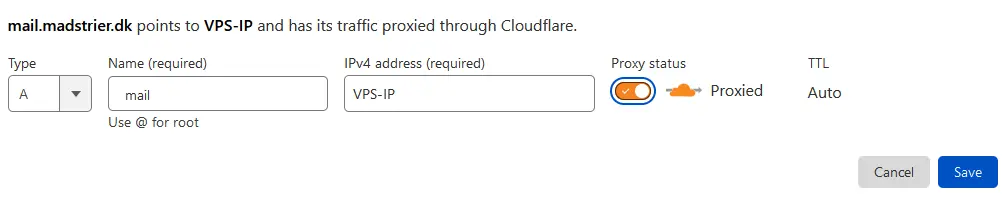

First things first, A-record. DNS A-records are used to resolve an IP-address (1.2.3.4) to a domain (example.com). We want our mail-domain (mail.example.com) to resolve to our VPS. Get your VPS’ IP from the control panel and navigate to your DNS providers control panel. I’m using Cloudflare as my DNS provider.

Ensure the Type is set to A. If needed, you can add a AAAA-record for IPv6. I won’t do this, since I don’t have IPv6 networking. Under Name, write your mail-subdomain name. On Cloudflare, you don’t need to write the entire domain name, only the subdomain part. On IPv4 address, input your VPS’ IPv4-address.

Note: If you want, you can proxy the entire website through Cloudflare. This can help prevent DDoS attacks and hide your VPS’ IP. However, for mail-servers, this is usually a bad idea. You risk your e-mail not being delivered or having errors.

MX-record

Next, MX-record. This determines which domains can handle e-mails for your root-domain. So, when you send an e-mail to admin@domain.com, a mail-server will handle that e-mail. This mail-server is determined from the MX-record. Multiple MX-records can be added for redundancy and load-balancing. That’s why you can specify a Priority. Multiple MX-records can have the same Priority, which will split the load evenly.

Ensure the Type is set to MX. Under Name, you can either write your root-domain, or @ if you’re using Cloudflare. Then, put your mail-domain under Mail server. The Mail server must not point to a CNAME or IPv4-address. Under Priority, 10 is usually used. Why? I don’t know. Anyway, a lower priority will make the mail-server preferred.

Installation

Here is where you should be configuring and installing your mail solution. I won’t go into too much detail, as it might change over time and it depends on which solution you’re rolling with.

If you’re using Mailu, they have a neat setup page here.

Mailcow users can find a guide here, in the documentation.

Done! Right..?

Oh, young student. With the current setup, you will technically be able to send and receive e-mail. But, you might notice… It’s all going to Spam!

Currently, no security measures are in place. You might not even have TLS! Services like Gmail have no way of proving the mail is legit, you’re prone to MITM attacks and you will have an all-around bad experience.

There’s a number of things that you’ll need to get, until you can even hope to send secure mail:

- TLS

- SPF

- DKIM

- DMARC

- TLSA/DANE

- (Optional) SRV for autodiscover

You might say “Gee wiz, Max, that’s a lot of stuff!” And you’d be right. But, don’t worry, some of these will be a piece of cake. Most of them are just simple DNS-records.

TLS

Let’s continue with a commonly used addition, TLS. Almost every single website you see on Google is encrypted with TLS. And, if you want to send mail, you better have it. Buying SSL certificates might be useful for some, but for a self-hosted solution, Let’s Encrypt is most likely the better option.

For Let’s Encrypt, you have 2 options. Either request a wildcard certificate or listing every subdomain under a single certificate. The latter requires the least setup.

Either which one you choose, tons of write-ups explain it better than I can:

- Individual Subdomains: Tutorial by Brian Boucheron

- Wildcard certificate: Write-up by Richard

I won’t go in-depth on how to install them, as tons of guides already exist. If you’re in doubt, search it up.

When you’ve confirmed that TLS/SSL is running on your HTTP server - be it Apache, Nginx or otherwise - you can move on to DNS, again.

DNS, Part 2: Electric Boogaloo

Going back to your DNS-provider, we’re gonna continue setting up records

SPF

So we determined which server to use for inbound mails using the MX-record. But, what about outbound? How can we determine whether which servers are allowed to send mails? Well, with the SPF record! The SPF record also determines which domains are allowed to send mail.

While your DNS provider might have a dedicated record-type for SPF, they’re usually obsoleted in favor of TXT-records (RFC-7208). TXT-records are used to display any kind of information, at a specific selector.

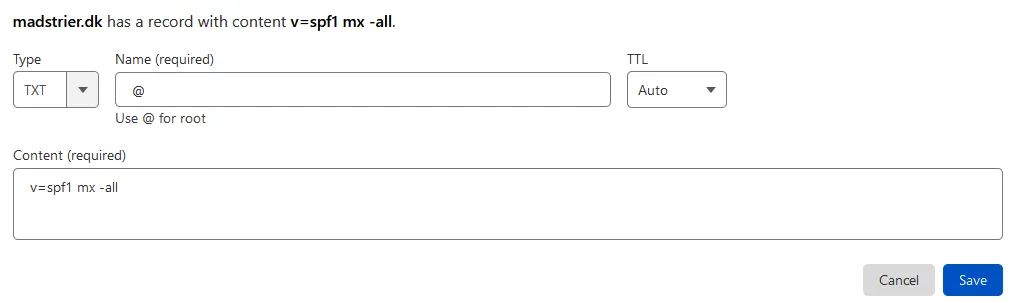

Let’s start by allowing our root-domain to send mail.

Again, ensure Type is set to TXT. Under Name, write the root-domain name or @, if using Cloudflare. This will match mails like admin@maxtrier.dk, but not admin@mail.maxrier.dk. If you want to use a subdomain in your mail, write that subdomain in Name.

Now, under Content, we need to specify a tiny bit.

v=spf1: Use SPF version 1. Version 2 did exist, but is now obsolete. No idea why, don’t ask.

mx: Allows the MX-server of Name (the root-domain, in this case) to send mail.

-all: All other IPs must fail.

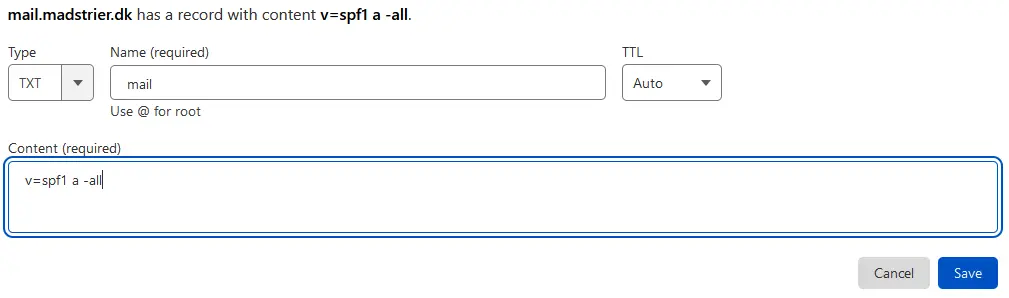

Next up, the mail-subdomain.

Much like above, we specify v=spf1 as the version, but instead of mx, we write a. This simply means, instead of allowing the MX-server of the root-domain, just use the A-record of this domain, which is the mail-server. And, again, fail any mails that don’t match with -all.

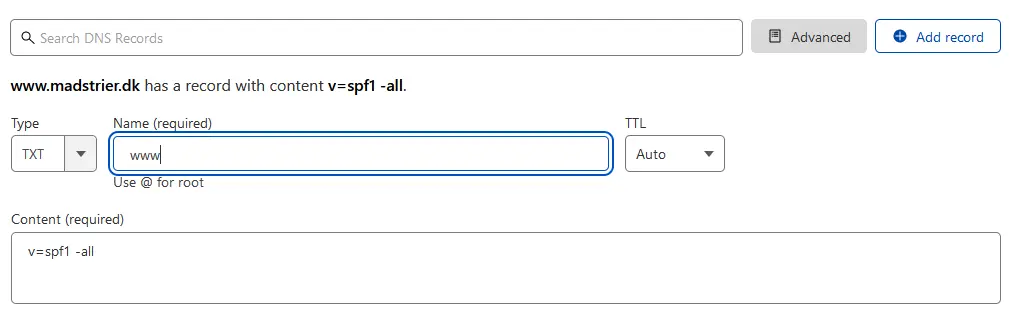

It’s good riddance to disallow any other domains that aren’t supposed to send mail, such as login.maxtrier.dk or others, from sending mail. This includes the www.-“sub-domain”.

Here, we don’t match anything. Simply drop all mails coming from www.maxtrier.dk. If you don’t have this or any other subdomains, then skip it.

DKIM

Next, DomainKeys Identified Mail (DKIM). DKIM is used to determine whether an email came from the sending domain or if it was forged. DKIM uses a cryptographic keypair, which includes a private key and a public key. The public key is included in a TXT-record on the root-domain. The receiver can then verify the sender of the mail.

DKIM keys are usually handled by your mail-solution. It will therefore change with each solution. Since I use Mailu, I’ll show how to get the DKIM public from there. If you’re using any other solution, read the documentation or fumble around with the admin control panel.

In Mailu: The DKIM public key is found at Admin Panel > Mail Domains > Details (in the table) > DKIM public key

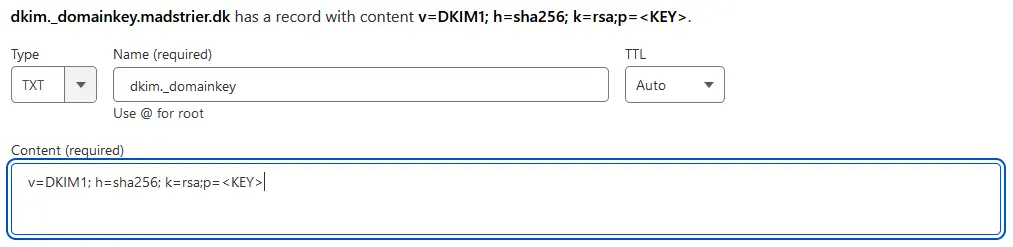

Once you have the key, make a new TXT-record:

Under Name, enter “dkim._domainkey” and under Content write:

v=DKIM1; h=sha256; k=rsa;p=<KEY>Replace <KEY> with your DKIM public key. And done!

DMARC

Next up is “Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting and Conformance” or DMARC. DMARC is used to handle unauthorized use of a mail-domain, by utilizing SPF and DKIM. It tells receiving servers how to handle with failures and who to message, in case of errors.

DMARC is also a bit special, because it actually requires 2 records. One to handle errors and one to enable reports.

Let’s start with the error-handling record.

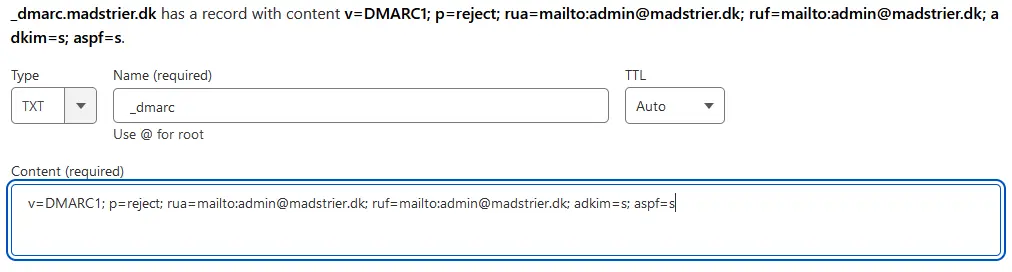

Use “_dmarc” as Name and use the following as Content:

v=DMARC1; p=reject; rua=mailto:<aggregate>; ruf=mailto:<forensic>; adkim=s; aspf=sLike SPF, we define the DMARC-version as version 1. Next, what to do with mails that fail the DMARC-check. We use “reject” as using anything else, might lower your mail-credibility. As said before, DMARC allows for reporting of errors. One for Aggregate reports (rua) and one for Forensic reports (ruf). These values must be valid e-mails. Replace

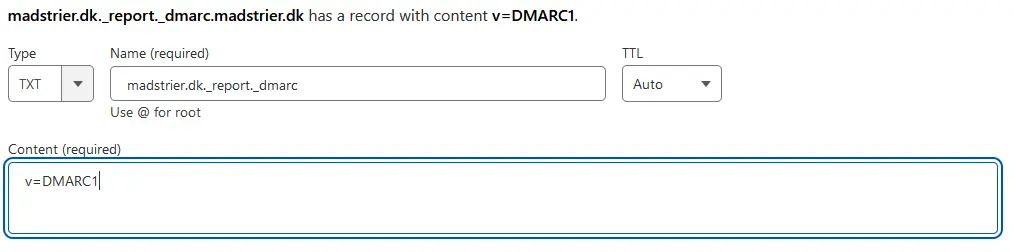

The second record is a lot simpler. Again, new TXT-record.

Under Name, put “<root-domain>._report._dmarc” after replacing “<root-domain>” with your own root-domain (such as maxtrier.dk). In Content, put “v=DMARC1”. Now you’re done with DMARC!

DNSSEC

DNSSEC is something special. It’s not a DNS-record, nor a simple program you can run. DNSSEC is a way of cryptographically signing the DNS-response you get from your DNS-server.

To enable it, you have to go to the control panel of your domain host. This is most likely not Cloudflare. Go to the website where you bought your domain and look around of “DNSSEC Keys” or something similar. It’s gonna ask for tons of options. If you’re using Cloudflare, they’ll tell you what to do.

Cloudflare DNS: When on the DNS-page of Cloudflare, scroll down ‘till you see “DNSSEC”. Click Enable and follow the instructions. Since I’ve already done this, I can’t repeat it. The next step requires DNSSEC to be enabled and working.

For any other DNS-provider, look around, search it up or ask support.

TLSA/DANE

TLSA is a way of storing a hash of the TLS-certificate in the DNS-settings. This is why it requires DNSSEC, as a compromised hash is worthless.

To generate the hash, we can use hash-slinger on Ubuntu (apt-get). This will give us the tlsa-binary.

# tlsa --create --selector 1 --certificate public-key.pem <root-domain>If you used Certbot to get a Let’s Encrypt certificate, you can do the following instead:

# tlsa --create --selector 1 --certificate /etc/letsencrypt/archive/<domain>/fullchain1.pem <root-domain>It’s important that you don’t point to the certificate in /etc/letsencrypt/live, as that’s a symbolic link and will give an invalid hash.

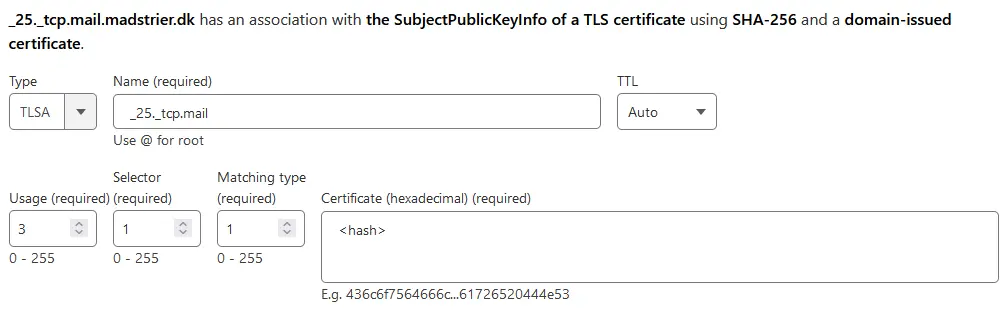

After you get your hash, add a TLSA-record in your DNS.

Here, we’re adding a TLSA-record for port 25/TCP, which is SMTP. Set Name to “_25._tcp.mail”, accordingly. Set Usage to 3, Selector to 1 and Matching type to 1. Afterward, paste the hash from earlier into Certificate.

If you want to certify any other ports, now is a good time to do it. I won’t go over it, as it’s a little repetitive. Ports might include 110/TCP (POP3) or 143/TCP (IMAP).

(Optional) SRV

Some mail-clients support “autodiscover”, which attempts to get the SMTP/IMAP hostnames from DNS. This requires a little setup, however. You need to create a couple of SRV-records, for all your services and a single SRV-record for autodiscover. It’s awfully repetitive, so I’ll give a quick example that you can repeat.

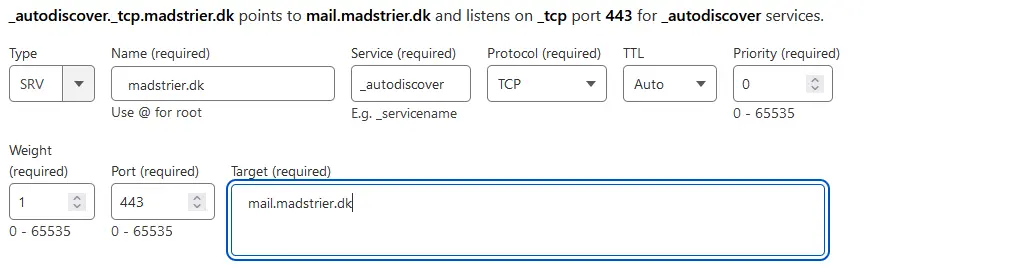

Firstly, you need to get autodiscover. Make a new SRV-record.

Ensure Type to SRV, set Name to your root-domain, Service to “_autodiscover”, Protocol to TCP, Priority to 0, Weight to 1 and Port to 443. Lastly, enter your mail-subdomain under Target. Now you have autodiscover-enabled! But, you haven’t set any SRV-records for any services, yet.

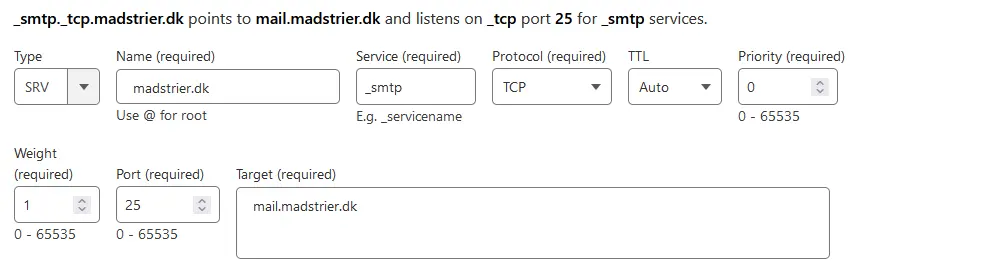

The steps below are meant to be repeated for all your services. So, this would mean IMAP, SMTP, POP3 and all the secure versions, too.

Again, make a new SRV-record, but set the Service and Port values to one of the values below:

| Service | Port |

|---|---|

| _stmp | 25 |

| _stmps | 465 |

| _submission | 587 |

| _imap | 143 |

| _imaps | 993 |

| _pop3 | 110 |

| _pop3s | 995 |

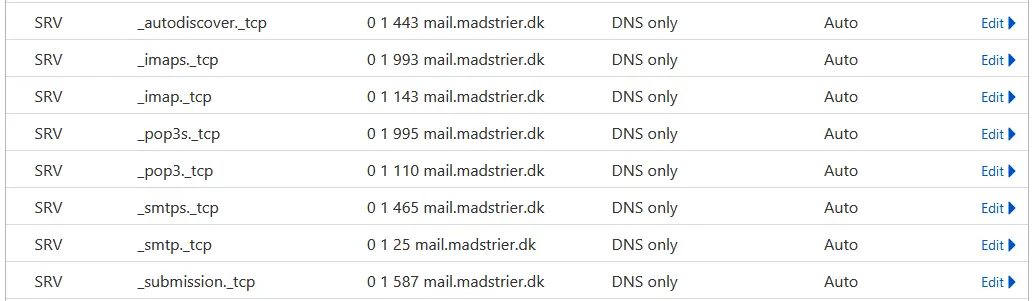

When you’re done, your DNS-table should look similar to this:

Wrapping Up and Troubleshooting

Finally done, yeah? Well, you’re never actually done with a mail-server. Now, there’s a handful of tools that you should try running your mail-server against, before deploying it.

This tool is amazing. It can detect pretty much any fails or non-optimized values in your DNS, configuration, etc. Some tools you should try from here are MX Lookup (note: enter your root-domain here), Blacklist Lookup, SPF/DKIM/DMARC Lookup, and Email Deliverability.

Note: When using the Blacklist-lookup, you might see your IP on some of these blocklists. That’s expected, if you have a VPS. Most of them have a corporate way of delisting yourself. There are, however, a couple that you shouldn’t bother with. This is mostly Blacklists that ask for money to unlist you. This includes UCEPROTECTL2/UCEPROTECTL3. Don’t bother, they’re scammers. Others are just super old.

- This tool is pretty great for measuring the spamminess of your mail. They’ll give you an autogenerated mail that you can send a test-mail to and they’ll give a report about it on the website. You should send an actually e-mail, as it also checks for the content of the mail. If that doesn’t matter to you, you can disregard the score and only look at the summary.

Microsoft Remote Connectivity Analyzer

- While not a catchy name, this tool will analyze your TLSA/DANE records and check the validity.

If there are any problems or mistakes in my writing, please do tell. You can contact me at the link at the top of the page.